As a child, the high point of my life used to be the storytelling sessions we had during summer vacations. When Preetha, Praveenchettan, Pramod, Rajesh, Dinesh and I gathered around Jagdish (or Jagguettan, as we call him; our eldest cousin on my father’s side), listening in rapt silence to the stories he told us. No one, but no one, told a story like he did.

In a matter of minutes, he could make the walls of the small side room in Krishna Vihar disappear. And I would be standing on an unpaved street in the Wild West, watching Clint Eastwood enter, eyes screwed up against the sun, a cigar dangling from the side of his mouth… I would see his hat and poncho, his black horse, the taunting men…Now he is taking out his gun and— Dhishkyaun! My heart would jump to my mouth even as the bad guys lay dead on the ground. Jagguettan could, with the same ease, take me to a studio in the Greenwich Village where Jhonsy would be looking out of the window and counting the leaves on the ivy vine opposite. And when Sue revealed Behrman’s masterpiece, my eyes would sting with tears too embarrassed to flow out.

Jagguettan, with his endless supply of stories, trivia and comic books, used to be my hero. This, despite the fact that he had once declared me dead, while showing me how to find the pulse point on my wrist. After probing my then-skinny wrist for a good minute, he let go of it with a shake of his head. “No pulse,” he informed. “You’re dead!”

***

Growing up deprives you of a lot. For one, it takes you far away from cousins who tell stories. And when life decides its time for you to grow up, it comes at your bubble with a sledgehammer. All you can do is to quietly fold and pack the broken pieces of your childhood and stow them out of sight – in the farthest corner of your heart. Then you turn to books, a small part of you forever seeking your master storyteller between their pages. In hope.

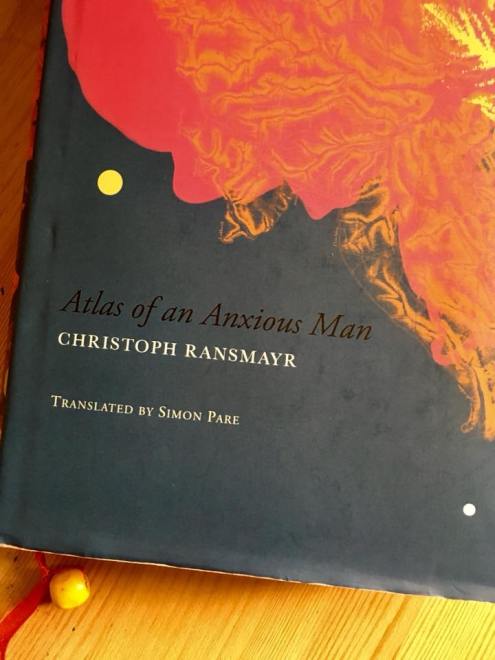

Then one day, another lifetime or so later, comes a book. “I saw the home of a god at latitude 28º28′ south and longitude 105º21′ west — a deserted rock crowded with seabirds far, far out in the Pacific,” it begins. Your ears perk up. That voice – you know it! You’ve heard it before, in an almost-forgotten past. You read on, now eager, hopeful. And as the “…wave-battered, treeless, bush-less cliffs devoid of fresh water, grass, flowering plants and moss” unfurl before you, you realise with a thrill that it’s him, your Great Storyteller. You’ve found him again, inside the covers of this magical book titled ‘Atlas of an Anxious Man’.

You are, once again, that wide-eyed child standing at the open gates of wonderland.

As Christoph Ransmayr begins each story with “I saw…”, I see what he saw. I see people – living, dying and long-dead. I see oceans, islands, rainforests and polar ice caps. Icy peaks, salmon-filled rivers and volcanic lakes. Abandoned graveyards, sunken ships, and remains of ancient civilizations. I hear batwings, birdsongs, and five laughing men. And sometimes, as when I see “an empty park bench, one of three on the market square beside the wrought-iron fence of the adjacent apothecary garden in the village of Lambach in Upper Austria,” my eyes fill up.

Translated by Simon Pare for Seagull Books, the note in the jacket modestly describes Atlas of an Anxious Man as a ‘unique account that follows (its author) across the globe’. I would rather call it a book of stories. Stories woven out of Ransmayr’s experiences as an involved observer of people, places and events. Stories of love, grief, courage, heartbreak and lasting hope. Narrated as if to a group of close friends gathered around the fireplace on a cold evening.

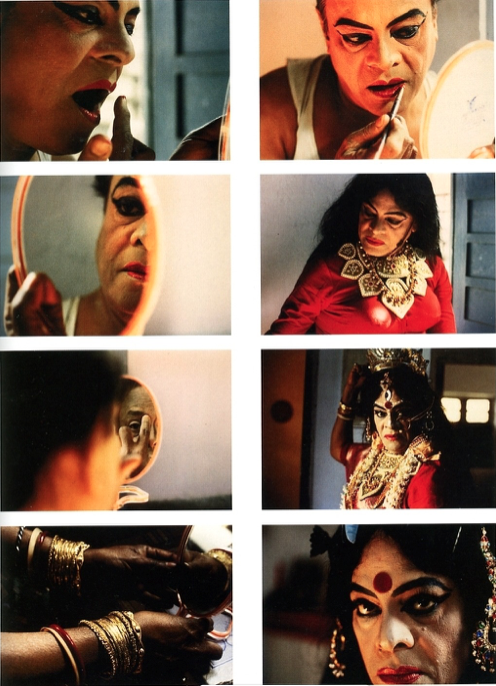

The text inside the gorgeous jacket designed by Sunandini Banerjee is lyrical. It meanders unhurriedly through the many geographies Ransmayr has visited, pausing every so often to admire a garden or a graveyard, talk to its keeper, or listen to the sound of a sheepdog barking at a distance. The journey that starts from that first barren island 3,200 kilometres off the Chilian coast continues in no particular order across oceans, islands, mountains and continents, across treeless hillsides and tropical rainforests, across countrysides, cities and suburbs, until it reaches its lofty destination. As if the author is opening his atlas at random pages to shows us what he saw there.

“This crater, riven by erosion and tectonics, and half collapsed, resembled a skewed cauldron whose contents – a small house with a corrugated-iron roof, animal sheds, a barn and, above all, bellowing cattle and skin and bone horses on stony, black pastures – were about to be tipped into the sea. The cauldron’s lower rim lay so close to the surf that it was flecked again and again with flakes of spray whereas the upper edge of the crater faded away high above the breakers into scudding patches of fog.”

And I see it all. Every little thing.

Geography, however, is just one facet – albeit an intensely alive one – of this gem. There is also history, anthropology, politics, biology and astronomy. Philosophy too, among other things, woven intricately into the narrative by this master craftsman. Ultimately, Atlas of an Anxious Man is about human beings, as they come.

“I saw the dark, sweaty face of the fisherman Ho Doeun on a stormy November night in Phnom Penh. The capital of the Kingdom of Cambodia was celebrating the water festival that night. Ho was kneeling on the bank of the Mekong, under the sparkling bouquets of fireworks whose flaming arches and bridges of light spanned the river for two or three heartbeats before fading away in a thundering spectacle of colour.”

What makes this book so exceptional to me, however, is the silken thread of compassion that runs through the length of its narrative. There is no judgment – none at all. The man who narrates these stories has already made his peace with vagaries, both human and otherwise. He is merely telling us what he saw, heard, felt and remembered.

“…an autumn bird no longer really had to impress anyone very much. It sang, when it sang, more for itself than for or against another bird.”

And if I feel a lingering sense of melancholy after turning the last page, it could be because the afterglow has lit up some forgotten corners of my soul – where the wait for the next Great Storyteller has resumed.