The-need-to-get-away hammered against my brain like an untimely downpour even before I was fully awake. Real world was lurking outside my closed eyes and I did not want to face it. Not on that particular Sunday morning. I needed to escape, and not into Netflix or Prime Video. I had to go out. Out of my orbit. Alone.

“Do it ‘Ma.” My firstborn, aiding and abetting me over our WhatsApp chat. His faith in my capabilities is touching. I looked at my feet on the bathroom floor. Scarred, discoloured, battle worn. They had lived through more than their fair share of misery and pain. Yet they’d see me through. I hoped.

Google helped with the where and the how-to. Fort Kochi/Mattancherry, of course. Most sensible, time wise and money wise. And I never tire of the place.

The boat ride from Jetty was two and half songs long: the first a morose half of some modern Malayalam poem, followed abruptly by tinny versions of ‘choonariyaan ud ud gayi‘ and ‘yaad piya ki aane lagi‘ in rapid succession. Possibly for the benefit of the North Indian crowd that dominated the boat. Thankfully, we reached before the next song could begin.

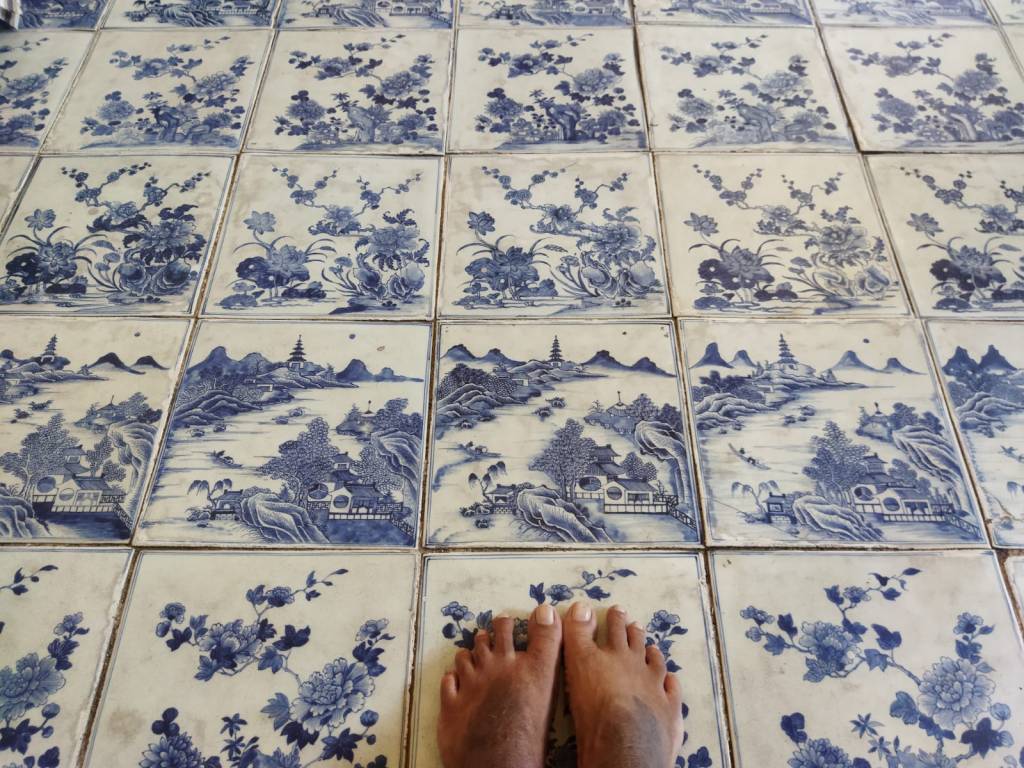

From Fort Kochi jetty, I took an auto rickshaw to Paradesi Synagogue. I like going there – for the history, the blue handmade tiles below, the lovely glass-and-silver chandeliers above, and the air of lostness and stuck-in-time-ness captured in crisp Hebrew letters.

There’s an affinity I feel for the ancient. They are repositories for stories. I even like myself better now that I did thirty years ago!

A photo wall with its David’s star to the right hand side of the entrance seemed like a new addition. I didn’t click a picture there. I just stood there wondering how a people that came peaceably to ask for refuge in a distant nation could inflict such unspeakable horrors on another.

I sat down on one of the benches inside the synagogue, and took in the tiles, the chandeliers and the sharp lines of the Hebrew words. Then walked around rereading the information on the walls. None of the information was new, but I was certain to have missed some of it earlier. The thing is, I invariably miss out details while reading or watching stuff – which is why I tend to reread books and revisit places. There’s always something new to discover. Maybe that’s the good part of ADHD: the perpetual newness.

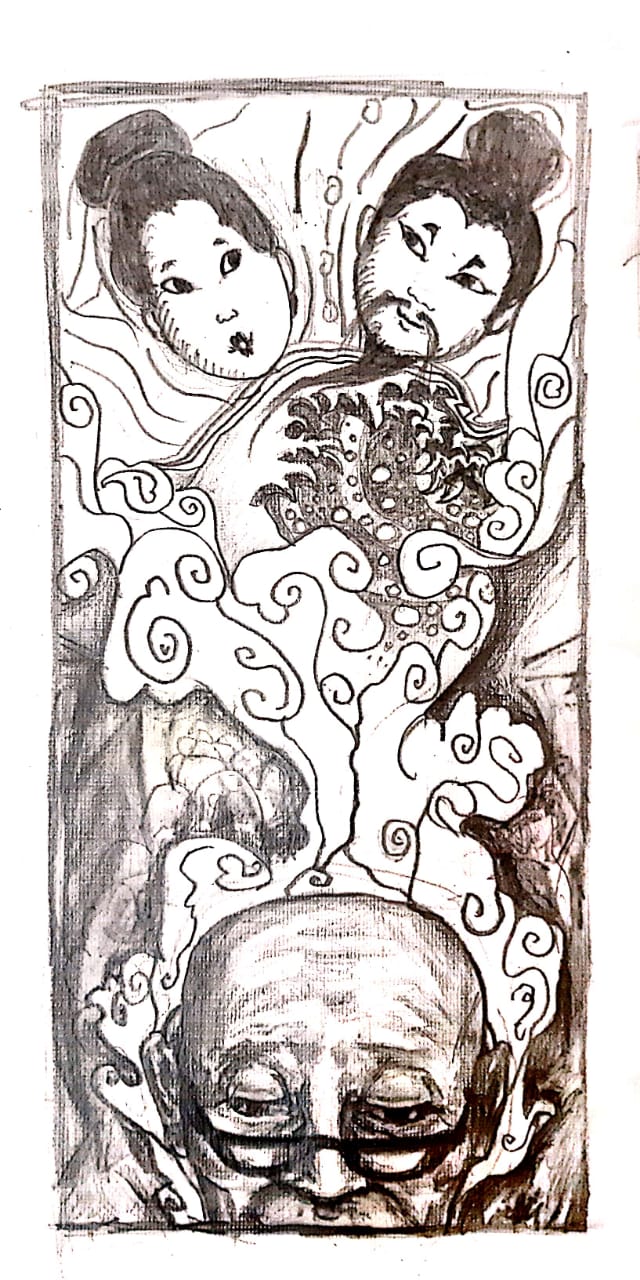

An art cafe close to the synagogue had art exhibition in an art and antique shop, so I decided to go in. Art made for poor breakfast, I suppose, so the gallery was closed, until a kindly staff member opened it for me. The paintings themselves were mild to moderate on the scale of interesting. The space, a remnant of colonial architecture, definitely scored higher.

The ground floor had an art shop on one side, manned by a man in an artist-looking attire. He looked up from his newspaper, decided that I was not worth his time, and went back to his reading. His work (if it was his, that is) was certainly worth mine, so I looked around.

Resisting the temptation of the million costume jewellery shops on either side of the street, I found my way to Ginger House, the restaurant that I had earlier on decided to grace with my presence.

A long, dimly lit hallway waited beyond the entrance, flanked by ancient-looking statues on both sides. To the left was an antique shop. A moment ago, I had witnessed the saleslady turning away a young, eager looking couple saying that this was not just a shop, but a part of the big restaurant beyond, in case they didn’t know. Her tone implied that the restaurant might be out of their budget. Snobbery thrives well in Kochi’s humid weather.

So, just for the kick of it, I put on my best non-Malayali, pan-Indian look and accent (trust me, I’m a pro at it when push comes to shove), smiled at the saleslady, and asked her if I could look around and take pictures. She smiled a little unsure smile, gave me a once-over, and reluctantly told me to go ahead, though taking photos was not allowed, technically. I thanked her again, clicked some pics, and headed over to the restaurant. Past painted gods under spotlights, artfully placed antique pillars, and creepers spilling over with flowers.

A large, spacious, curving verandah lay at the end of the walkway, with sea on one side and an idyllic garden on the other. A stone Nandi sat peaceably near the remains of a vintage car, and a horse head was engaged in mute, frozen conversation with a plaster of Paris peacock. Other stone and wood creatures grazed amidst casually trained creepers and stone/metal benches. A stellar space. Calm, calming, and incredibly beautiful. Whoever did up Ginger House has my undying admiration.

I sat down at a wooden table, directly under a ceiling fan. Out of respect for the restaurant’s name, I ordered a glass of ginger lime, which turned out to be limey and gingery to a fault. The ‘red pasta’ ordered for main course was more red than pasta: a handful of penne, fusili and traces of overcooked vegetables drowning in a violent, gleaming, orange-red sauce that screamed of vinegar.

I had read reviews online about the food being ‘overpriced yet mediocre’. A rather kind assessment, considering. But then I didn’t go there for the food.

I took my time with lunch, washed down traces of vinegar on the tongue with stronger traces of lime juice in the pretext of black tea, paid the king’s ransom that the smiling waiter demanded, and left – vowing to return.

Noushad, the auto driver that responded to my raised hand, hid his disappointment behind a wide, friendly smile when I informed him that I did not intend to do further sightseeing that day. He did manage to cajole me into visiting the All Spices Market on the way back, though.

The oversized, dilapidated doorway of the market opened out to a cavernous courtyard. There was no visible human activity, though the air was dense with myriad fragrances of familiar spices. I hesitated at the entrance, wondering about my chances of featuring in the next day’s local news. Middle Aged Woman Found—

There was an algae filled well near the entrance, with large cement vats next to it, – used to wash ginger ahead of drying, I was told. A figure in a dark blue sari came out of what looked like a granary on one side and squinted at us. Reassured, I followed Noushad into the courtyard, towards where a strong, gravelly aroma of pepper was wafting from. Subhadra, the woman in blue, was drying out crushed pepper, tons of which were waiting in sacks in the dimly lit granary.

Beyond the granary were some overgrown ruins, familiar through some Malayalam movies that I couldn’t recall the names of. Noushad took some touristy photographs at my request, after which we went to the shop upstairs to buy spices. When I insisted that I couldn’t ‘tourist’ anymore, he once again hid his disappointment behind his unfaltering smile and dropped me off at the boat jetty.

It was exhaustingly hot by then, yet the elation I felt was indescribable. The world suddenly seemed a nicer place, and I found myself smiling at complete strangers.

They say that you truly appreciate the value of something only when you are deprived of it. It had taken me more than three years of severely compromised mobility and complete disintegration of confidence, but I understood all too well how precious and beautiful a functional body was. And on that Sunday afternoon, as I stood waiting in queue for the boat, what I felt was profound gratitude.

Yesterday was Tough – with a capital T. My right eye started itching suddenly the night before, and in a matter of minutes became a purplish blob with a red slit in the middle. When the itch extended to my throat, I swallowed an antihistamine, and that sealed my misery. Spent the night tossing and turning in a restless half sleep, and was unable to pick myself up from the bed most of yesterday.

Yesterday was Tough – with a capital T. My right eye started itching suddenly the night before, and in a matter of minutes became a purplish blob with a red slit in the middle. When the itch extended to my throat, I swallowed an antihistamine, and that sealed my misery. Spent the night tossing and turning in a restless half sleep, and was unable to pick myself up from the bed most of yesterday.

.

.

We were on the Singapore Metro (or the ‘MRT’, as Amy calls it), though I can’t recall where we were going to, nor the name of the station we were to get down at. The train was quite crowded, so we stood to one side of the door.

We were on the Singapore Metro (or the ‘MRT’, as Amy calls it), though I can’t recall where we were going to, nor the name of the station we were to get down at. The train was quite crowded, so we stood to one side of the door.