Among the many items I had left behind of my childhood are some dialects. About half a dozen of them, in fact. Very peculiar to the times, micro-geographies and cultures of the places I grew up in. Dialects that smelled of green fields and steaming paddy. Of cow-dung, rain and persistent anxiety. Of palm-trees and claustrophobia of the wide open spaces, and a loneliness that stuck to your clothes like the yellow, gluey mud you scratched off the sides of the lotus pond.

“Enthinaanu thambraatti agiranathu? Namma ippo veettilethoolle?”

At the time I’d not even noticed the peculiarity of the lingo in which almost every vowel sound began and ended with the close-mid sound of ‘ɘ’. It was just a part of the landscape, like the greenness of the field or the blueness of the mountain, like the humid heat or the dark, lean bodies with their stench of sweat.

I’d just nod, not really sure why my eyes had filled up in the first place. Was I missing home or was I anxious about reaching it? I still don’t know.

Somewhere along the way, I made a choice – that of selective memory. Which meant that I let go of a lot of my childhood, including its dialects. I chose my memories in the order of their sunshine, and wove my narrative around them. I carefully picked the vocabulary, tone, and semantics of all the languages and their variations that had flowed past me, and created my own lingo. So now I have a set of streamlined memories that I can look back on and smile, and a language that rarely prods sleeping dogs. Malayalam with a hint of Tamil, which could have originated anywhere between the banks of the Nila and the blue shadows of Western Ghats. Liberally peppered with the English of all those cities I have lived, loved and read in.

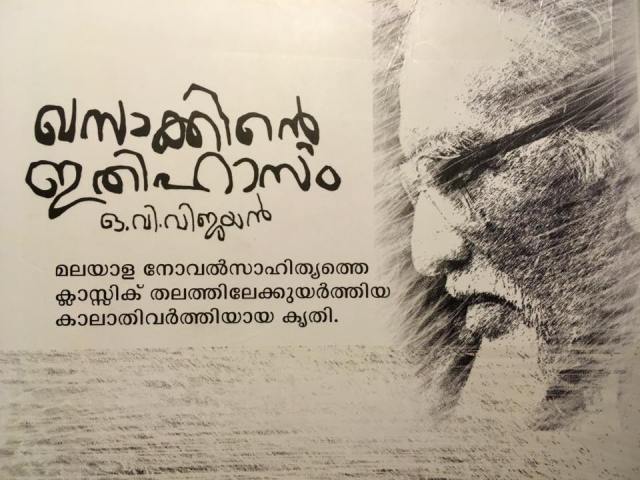

Perhaps that was why rereading Khasakkinte Ithihasam (Legends of Khasak) was like a punch in the gut.

True. Like any self-respecting Malayali teenager with intellectual aspirations (pretensions?), I too had read O.V. Vijayan’s epic while still in school. But what I had never admitted to anyone was that most of what was in there had flown right past me without leaving a dent. I had understood little, and I remembered even less. When people spoke so highly of it, I would nod in agreement, embarrassed that I had nothing to contribute to the conversation.

The other day, while browsing through the collection in a tiny DC Books store in Karama, I picked up Khasakkinte Ithihasam again. A burst of enthusiasm triggered as much by the prices, as by the cover illustration. And of course, sheer curiosity. What is in there that has triggered so much dialogue for so many decades?

Life comes back to where it started – in one way or the other. The world I had eased myself out of enveloped me again like quagmire, oozing out of the 168 pages of the O.V. Vijayan’s classic novel. Only now, with almost half a century of life behind me, there is no way I can escape the vagaries of Khasak.

There is little I can say about the book that has not been said before.

Ravi is familiar – a young, literate, well-read man from a reasonably well-to-do family, in the throes of existential crisis. The quintessential protagonist of Malayalam literature of the time. I have met him in various forms and names between the pages of the many novels I have read. Vijayan, however, does not make any concessions for Ravi, unlike some other ‘heroes’ of that era. He is what he is by choice. Or compulsion – take your pick. But the last thing he needs is your sympathy.

What Vijayan narrates, however, is not Ravi’s story – it is the history of Khasak in all its myriad, yet dark, hues. Madhavan Nair, Appukkili, Mollakka, Nijaamali, Mymoona, Chandumma, Kunjaamina…. the list of Khasak’s children is endless, and each one plays a vital role in taking the narrative forward. Even the ghosts, gods and folklore of Khasak are living, breathing entities in Vijayan’s eerily familiar world, as real as it is imaginary. A world that is raw, primal and open to the elements.

Which, like life, brings me back to where I started – the dialect. It was the Malayalam that Vijayan has chosen for his epic that took me by the scruff of my neck. And it dropped me right in the middle of a world that I had safely stayed away from for decades. A very Khasak-like universe where a third of my memories (because my idea of ‘home’ was split three-ways during my growing up years) are set in.

“Ootareelu Jayettande padau odunundu. Namukku puggua thambraa?”

Pazhanimala would tether the bullocks to the cart and we would go to the theatrein Oottarawith its thatched roof and stained screen to watch Jayan seducing married women with his pecs and biceps. Mutton biriyani from Rahmania Hotel after, and a return journey under the starry, starry sky, with the tinkle of little brass bells lulling me to sleep…

If all was well that is.

A stray memory that drifted in.

There is a Khasak napping inside me, like there is in so many others. And it has now become restless.

Every good prose, I feel, has poetry running through it like a golden thread. It is there in a turn of phrase, a line that you want to utter out loud. Poetry lingers like melancholy in Vijayan’s writing, woven into the harsh overtones of its vernacular, adding to its poignancy, its earthy shadows. Touching you in a way that only poetry can.

If the hallmark of good literature is to disturb the reader, to shake them out of complacency, then it’s little wonder that Khasakkinte Ithihasam continues to revive and thrive, decade after decade.